The Music Producer Outlook on AI, Music, and the Industry

Written by

Published on

January 26, 2026

Introduction: Every New Tool Was a Threat Once

Spend enough time around musicians and producers, and you’ll start to notice a pattern.

Every few decades, a new piece of technology enters the creative process and triggers the same reactions: This isn’t real music. This is cheating. This will replace musicians. The language changes slightly, but the emotion rarely does.

Today, that conversation centers on AI. From vocal generation to mastering assistance, AI tools have sparked a familiar mix of curiosity, skepticism, and outright resistance. For some producers, they represent an exciting new creative frontier. For others, they feel like a step too far, blurring the line between assistance and authorship.

But this dynamic isn’t new.

Long before AI entered the conversation, producers wrestled with similar questions around sampling, multitrack recording, drum machines, MIDI, pitch correction, and digital audio workstations. Each of these tools reshaped how music was made, and each faced backlash before becoming standard practice.

This article isn’t about predicting where AI will take the music industry next, or convincing anyone to adopt it. Instead, it’s about stepping back and looking at the bigger picture. By examining how producers and the industry have responded to major tech shifts over the last 70–80 years, we can better understand what feels familiar about the current moment—and what, if anything, is genuinely different this time around.

Multitrack Recording Redefines Performance (1950s–60s)

What changed: Before multitrack recording, a record was largely a document of a performance. Musicians played together in a room, engineers captured the moment, and mistakes were part of the final result.

Multitrack recording changed that relationship entirely. Early innovators like Les Paul helped popularize multitrack recording in the 1950s, demonstrating that the studio itself could be used as a compositional tool rather than just a place to document live performances.

By allowing individual parts to be recorded separately and layered over time, musicians and producers could now construct a performance rather than simply capture one. Timing issues could be fixed. Vocal takes could be comped. Arrangements could evolve long after the musicians had left the studio.

This marked one of the first major shifts toward the modern idea of production, where records are assembled deliberately, piece by piece, rather than performed start to finish.

How the industry reacted: Not everyone welcomed the change.

Early critics argued that multitracking removed the human element from music, encouraging musicians to rely on editing instead of skill. If a performance could be endlessly corrected and rearranged, what did “authentic” even mean anymore?

These debates struck at the identity of musicians who had built their craft around live performance and feel. Technology, in this context, felt less like a tool and more like a challenge to musicianship itself.

The Studio Becomes a Creative Instrument

Despite the resistance, multitrack recording didn’t dilute creativity. Instead, it expanded it.

Producers began using the studio as an instrument, experimenting with arrangement, texture, and sound design in ways that were impossible before. The constraints and possibilities of recording technology have always influenced the way producers work. Over time, multitracking became so foundational that it’s now difficult to imagine modern music without it.

This shift set a precedent the industry would encounter again and again: when technology alters how music is made, it often forces a deeper conversation about who is being replaced, and who is being empowered.

Drum Machines & Sequencers Introduce Automation (1970s–80s)

What changed: Drum machines introduced a radical idea: rhythm no longer had to come from a human performance. With programmable patterns and precise timing, producers could build grooves that were perfectly consistent, or intentionally rigid in ways no human drummer could sustain.

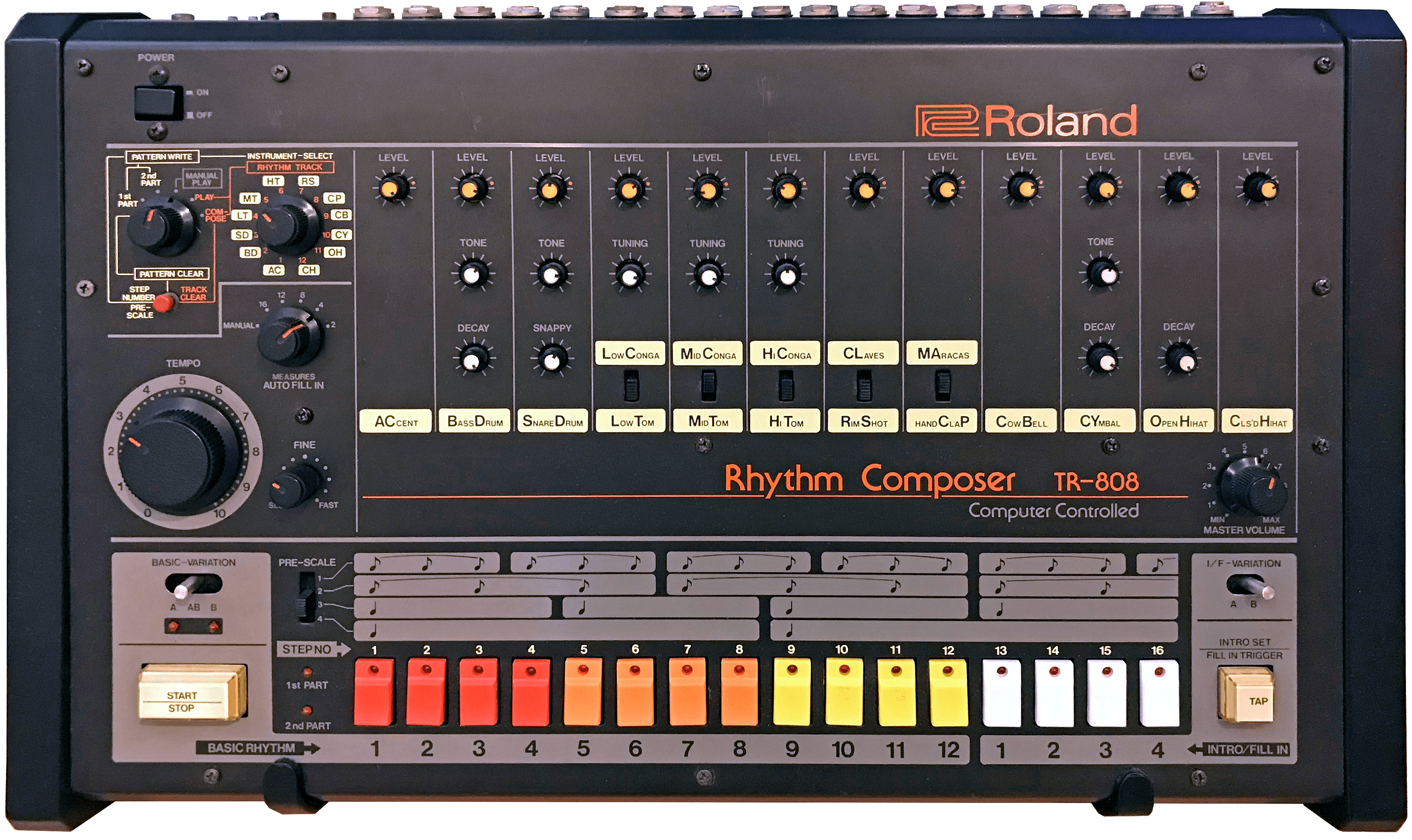

While early programmable machines like the Eko ComputeRhythm laid the groundwork, it was the Roland TR-808 that brought drum machines into widespread use, shaping genres from hip-hop to electronic music and remaining influential today through modern software emulations.

The Roland TR-808 drum machine released by Roland Corporation between 1980 and 1983

This shift changed who could make rhythm-driven music at all. You no longer needed a drummer, a room, or even a band to experiment with beats. Rhythm became something you could design.

How the industry reacted: The backlash was immediate and emotional.

Drum machines were accused of being cold, mechanical, and soulless. Many feared they would replace drummers entirely, stripping music of its human feel. For working musicians, the anxiety was practical as much as artistic: fewer players needed meant fewer jobs.

At the time, it felt like automation was stepping directly into creative territory that had always belonged to people.

When Automation Gave Birth to Entirely New Genres

Instead of killing rhythm sections, drum machines helped create entirely new musical languages and genres.

Hip-hop, techno, electro, and many forms of pop grew directly out of programmable rhythm. Human drummers didn’t disappear. They adapted by incorporating electronic elements or carving out new roles alongside machines.

The addition of multi-track recording along with the advent of drum machines, it became clear that music was moving closer to a world where ideas could be edited, rearranged, and refined after the moment of performance, setting the stage for an even more abstract shift.

MIDI Turns Music into Data (1983)

What changed: The introduction of MIDI quietly transformed music more than almost any tool before or since.

Notes were no longer just sounds. They became instructions. Pitch, velocity, timing, and duration could all be edited after the fact. A performance could be recorded once and reshaped endlessly.

The MIDI standard created a shared technical language that allowed instruments and computers from different manufacturers to communicate for the first time, forming the backbone of modern digital production workflows.

A single keyboard could trigger an entire studio’s worth of instruments, virtual or physical, along with dynamics information like volume, sustain, and vibrato.

How the industry reacted: To many musicians, MIDI felt like a step away from performance and toward programming. Now we are starting to see a pattern in the reaction to the introduction of new music technology. Less performance and more programming.

Critics argued that editing MIDI erased feel and nuance, replacing expression with grids and numbers. Once again, the concern wasn’t only technical—it was about identity. If music could be rearranged like data, what happened to the value of playing well in the moment?

MIDI In Modern Production Workflows

Today, MIDI is so fundamental that it’s nearly invisible.

The real creative shift wasn’t the loss of expression altogether, but a shift in where that expression was channeled. This fundamentally changed how producers think about composition and control.

However, as music became editable data, a new question emerged: if sound could be endlessly reshaped, where did originality actually begin? That question would soon come to the forefront.

Sampling Challenges Ownership & Originality (Late 1980s–90s)

What changed: Sampling allowed producers to treat existing recordings as raw material. Sounds could be lifted, reshaped, looped, and recontextualized into something entirely new.

Early samplers like the Fairlight CMI, and later the Akai MPC, made it possible to capture, manipulate, and replay recorded sound, bringing sampling out of experimental studios and into mainstream music production.

For the first time, creativity and ownership collided head-on. Who owned a sound once it had been transformed? How much change was enough to make something original?

How the industry reacted: The response was chaotic. Early sampling culture collided with copyright law long before clear creative or legal standards existed.

Sampling was labeled theft. Lawsuits piled up. Artists and labels pushed back hard, arguing that this new approach undermined originality and devalued musicianship. The industry had no clear framework for handling creativity built on top of existing work.

YouTube: What is Sampling? | Music Production | Loudon Stearns | Beginner | Berklee Online posted by Berklee Online

From Legal Chaos to Creative Standards

Sampling didn’t disappear. It evolved.

Clearer rules emerged around licensing, clearance, and attribution. Sampling became recognized as its own art form, with boundaries shaped by law and culture rather than fear.

The key shift wasn’t whether sampling was allowed, but how it could be used responsibly.

With ownership frameworks slowly forming, technology continued moving in another direction. It did more than change what producers could do. It changed who could do it at all.

DAWs & Home Recording Democratize Production (1990s–2000s)

What changed: Digital audio workstations moved production out of expensive studios and into bedrooms, basements, and laptops.

Editing became non-destructive. Mistakes were reversible. Access to professional tools exploded almost overnight. You no longer needed a half-a-million dollar studio to make great sounding records anymore.

How the industry reacted: Once again, the same concerns surfaced.

If anyone could produce music, would quality suffer? Would professional standards collapse? Was being a “real producer” now just a matter of owning software?

The gatekeeping power of studios weakened, and with it, long-held ideas about legitimacy.

The End of Studio Gatekeeping

Early platforms like Pro Tools helped standardize digital recording in professional studios, while later software brought similar capabilities to independent creators working from home.

With access no longer a differentiator, results became the standard. Producers were judged less by where they worked and more by what they delivered. Competition increased, but so did innovation.

Instead of cheapening production as many critics expected, this new recording technology raised expectations and allowed for creating music cheaper and faster.

As the tools became faster and more accessible, the conversation shifted once again. This time, the focus shifted toward efficiency, shortcuts, and where skill truly lived in modern production.

Vocal Tuning, Presets & Workflow Acceleration (Late 1990s–2010s)

What changed: Pitch correction, presets, sample packs, and workflow-focused tools dramatically sped up production.

Technical barriers fell. More time could be spent shaping ideas instead of solving problems.

How the industry reacted: The familiar accusations returned. Vocal tuning and pitch editing was called cheating. Presets were dismissed as shortcuts. Concerns about sameness and loss of skill dominated the conversation.

When Taste Became the New Differentiator

These tools expanded the creative possibilities for both professional and amateur musicians and producers. It created new sounds and styles and, once again, allowed music creators to work more efficiently.

Originality moved into taste, context, and intention. The producer’s role became less about proving technical difficulty and more about making strong creative choices.

AI in Music: A Familiar Pattern with New Stakes

What feels familiar: Much of the reaction to AI sounds like echoes of the past.

Producers worry about automation replacing skill. Artists fear losing control over their creative identity. Critics question whether music made with AI can still be considered authentic.

These concerns have surfaced with every major tool shift examined so far.

What’s genuinely different: AI does introduce challenges that earlier technologies didn’t have to confront at the same scale.

Training data raises questions about consent and transparency. Voice models blur the line between inspiration and identity. And unlike earlier tools, AI systems can replicate style and likeness in ways that feel personal rather than technical.

These concerns aren’t theoretical. As outlined in the Recording Academy’s advocacy work on how music creators are pushing for clearer AI copyright protections, policymakers and industry groups are actively grappling with how copyright, consent, and creator rights should apply in an AI-driven landscape.

The issue isn’t simply what AI can do. It’s whether the systems behind it respect the people whose work and identity they rely on.

This distinction is why transparency around training data and consent matters. Some platforms, like Kits.ai, have taken a public stance on building and deploying tools using ethically trained models that prioritize creator permission and control, outlining that approach in their commitment to ethical AI practices for music creators.

The Producer's Evolving Role

Modern producers aren’t just creators anymore. They’re curators, decision-makers, and gatekeepers.

Choosing tools now means choosing values. AI can accelerate workflows and unlock new ideas, but it also demands intention. Used thoughtfully, it can support creativity. Used carelessly, it can hollow it out.

The difference isn’t the tool. It is the judgment behind it.

Conclusion

Looking back at decades of music technology, a clear pattern emerges. Tools change quickly. Reactions follow predictably. And over time, producers adapt. This doesn't mean abandoning values, but redefining how those values show up in new workflows and expanding creative possibilities.

Every turning point explored here raised concerns about authenticity, skill, and ownership. In most cases, those fears didn’t come true in the way people expected. What did change was where creative responsibility lived.

AI represents a new chapter in that story. It introduces real questions around consent, transparency, and identity that deserve careful consideration. But it also fits into a much longer tradition of tools designed to extend, accelerate, and support human creativity—not replace it.

For modern producers, the work remains the same: making intentional choices, developing taste, and staying accountable to the music and the people behind it. The tools may evolve, but authorship still belongs to those who decide how, when, and why those tools are used.

That philosophy—creativity first, responsibility always—is what ultimately determines whether new technology sinks or swims.

Justin is a Los Angeles based copywriter with over 16 years in the music industry, composing for hit TV shows and films, producing widely licensed tracks, and managing top music talent. He now creates compelling copy for brands and artists, and in his free time, enjoys painting, weightlifting, and playing soccer.